Curatorial Essay

Nancy Adajania

The tradition of the landscape, whether in the visual or the literary arts, has always articulated the desire to recover or reclaim the natural at the very moment when it is threatened with annihilation by the forces of economic change, architecture and technology. The Greek bucolic poets wrote even as the Hellenic city-states had begun to farm the wilderness into fields. The Roman pastoral poets wrote even as the Augustan Empire brought nature under the control of highways, canals and aqueducts. The Sanskrit poets crafted stunning allegories of nature even as the forests of the Gangetic river valleys were being cleared for cultivation.

In the visual arts, also, the vibrancy of landscape as subject has coincided with major technological revolutions that threatened to overrun nature. The Romantic and Impressionist engagements with landscape, for instance, coincide with major transformations of experience: even as colonial expansion, steam, electricity, and the railways changed the countryside forever, artists tried to address and capture the natural through the optics of the Sublime, of nostalgia, of social critique, or fantasia. Importantly, also, both the Romantics and the Impressionists maintained close links with science and technology, consulting meteorological almanacs, reading studies of light and accounts of experiments with locomotion and electricity, and keeping up with alternative or new media at every stage, whether tube paints, the telescope or the camera.

*

Today, the natural has been menaced or re-formatted by a new triad of forces: the media, militarisation, and surveillance. The media have turned nature into the readymades of exclusive holidays and postcard memories, broken it down into Facebook shareware, and presented it as a quilt of historic landmarks and intimate neighbourhoods, all rendered equally available on Google Earth. Militarisation subjugates nature with barbed-wire fencing, checkpoints, mine-fields and watchtowers. Surveillance, which marks the intersection of media and militarisation, also reduces the natural to a landscape of potential threats, footage to be scoured for signs of unrest and insurgency, whether that landscape is the hinterland or the metropolitan street.

Indeed, the landscape is no longer clearly designated by regional characteristics or specificities of cultural practice. It is a conceptual terrain, inscribed and re-inscribed by narratives that reshape it to their own purposes. The landscape, which was once the paradigm of location and belonging, is today a guarantee of uncertainty, disturbance, and disorientation. Thus, I arrive at my formulation of ‘The Landscapes of Where’ in relation to the work of five artists – Prajakta Palav Aher, Pooja Iranna, Prajakta Potnis Ponmany, Sonal Jain and Mriganka Madhukaillya. How do these artists position themselves and reclaim the landscape in a time of radical dislocation?

*

The Aladdin complex of globalisation ensures that we can rip images at will, click a button to add to our cave of treasures: Mount Fujiyama for the album, the Petronas Towers or a stretch of Michigan forest for a screen-saver, a piece of Californian sky to sleep under. We can transport the Taj Mahal to Colorado and dispatch snowflakes to Bangalore in our digital dreams. Every image becomes an archaeology of templates, waiting to be excavated, layer by layer. What then happens to our notions of ‘land’ in a landscape, to the placed-ness of place? Does ‘land’ become a composite image of recognisable and unrecognisable places: does it seem like our own but also like somebody else’s? But this litany concerning ‘elsewheres’ should not prompt the reader into the kind of alarmism that regards new technologies of digital manipulation as the work of the Devil.

It has been claimed that these technologies, pervasive in the era of globalisation, will impose an automatic cultural homogeneity, erase diversity, and diminish local autonomy. But in truth, new technologies enter a situation such as contemporary India at uneven rates of speed. They are assimilated and indigenised to various degrees, depending on local factors and regional parameters. Two of the participants in this exhibition – Palav and Iranna – deploy Photoshopping techniques to reshape images grabbed from the Net, or the print media, or, as in Iranna’s case, her own photographs. The results manifest differing notions of self, agency, social location and desire.

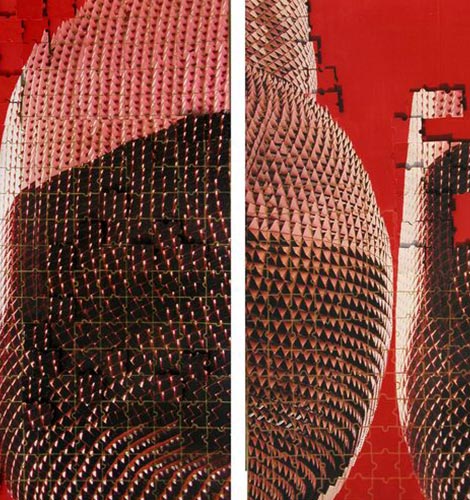

Prajakta Palav Aher’s recombinant landscapes evoke the beauty and terror of the Sublime by seamlessly stitching diverse elements together: for instance, she takes a ‘scenery’ sourced from Google Earth and melds it with the photograph of a mountain in a Bombay suburb that has become invisible beneath the overgrowth of slums that it now bears. These paintings deftly mongrelise our experience of landscape painting; they mimic the magisterial scale and presence of high art, but also refer to the angelic ‘sceneries’ (as they are described in many Indian regional languages, the word adapted from English), cheap landscape posters deployed by some sections of the middle class to decorate their homes.

This is not a cut-and-paste job made possible by the genies of globalisation. Palav manifests an intuitive vision – intuitive because she does not articulate it as such in words – of the counter-sublime. It is conveyed through the threatening abundance of the multitude, and the proliferating built form that overwhelms both the individual in the metropolis and the cosmos at large. [1] The viewer knows that the settlements on the mountain in the distance will stealthily rip through the sap green and viridian of the ambient landscape, erasing the memory of the earth’s skin forever. And the river will choke on the houses that will not stop growing. Apocalyptic events take place silently in Palav’s painting, just as they do in the paintings of that master landscapist Brueghel, who shows the farmer continuing to plough the field, the cattle grazing, and a ship sailing on, while Icarus falls unnoticed into the sea.

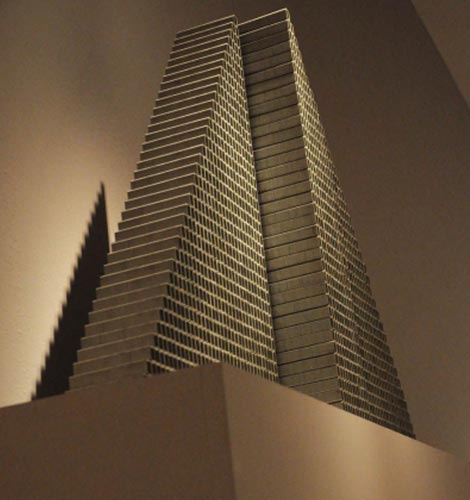

For Pooja Iranna, landscape becomes subsumed within an architecture that is hypermodern and is already the voluntary accomplice of media legend and surveillance regimes. Instead of sky, we see a skyscraper; instead of a river, we see a bridge; when we try and map our position, we see only ambient darkness. In the Photoshopped images of built form shot in the USA or Singapore, the structures are riffed and repeated to create a false perspective that invites us in and takes us captive. Or then the buildings are flipped over many times, geometries folded on geometries to form mirages, to disorient the viewer.

What Iranna develops in the course of these exercises is not the commemoration of structure so much as the deepening of bhava, a mood that eludes precise verbal explanation while yet generating unmistakeable sensuous response. Her works convey a spectrum of emotional temperatures, ranging from the fragile to the tough, the auratic sensation of beyondness to the quotidian awareness of light and darkness. In a melting black backdrop, a building floats like a bejewelled lantern, the faint presence of a crane suggesting the ongoing nature of Iranna’s ‘construction’ activity (Encountering Illusion II, 2008). By contrast, ‘Encountering’, 2008, signals a monster building that is seemingly ready to take off, a flying machine or menacing UFO that is paradoxically also a moving target. In Iranna’s work, the role of the landscape has been wholly usurped by an architecture of authoritarian control, as suspicious of airplanes straying from their flight paths as it is of unauthorised whispers in the street.

In the midst of the unpeopled landscapes of Palav and Iranna, an old couple sitting in a Shiva-Parvati pose suddenly materialise in a verdant meadow festooned with Mickey Mouse balloons. While they seem to be enjoying a yogic lightness of being, their modest, even rustic clothes do not match the holiday brochure backdrop that promises luxury and recreational ease. Imran, the technician at a streetside photo studio in Bombay, has Photoshopped the image in layers. His brief was to represent the couple as though they were on a tirtha-yatra, a religious pilgrimage. Instead of the conventional pilgrim destinations of Hardwar or Prayag-Allahabad, Imran chose a phantasmagoric template: he told me that he felt the old couple would feel comfortable in the open maidan-playground-like space with a river and colourful balloons and sent them on a pleasant fictional journey. He secularised the yatra by evacuating it of its religious content, replacing the pilgrimage centre with the holiday resort. In this new social play of fantasy, the conventional categories of nationality, ethnicity and religion can no longer usefully account for the identities that are being generated at various levels of the popular imagination.

I am left with a question: Who is the sva in the rupa, the self in the form? Is it Imran, or is it the photographer? Or is it the couple represented within the image? Or their children, the clients who produced the demand for a fitting visual tribute? ‘Yatra’ is an image produced by a complex coalition of desires. It challenges our regimented ways of understanding how culture is produced, and injects the virus of the demotic aesthetic more forcefully into the gallery space than before. [2]

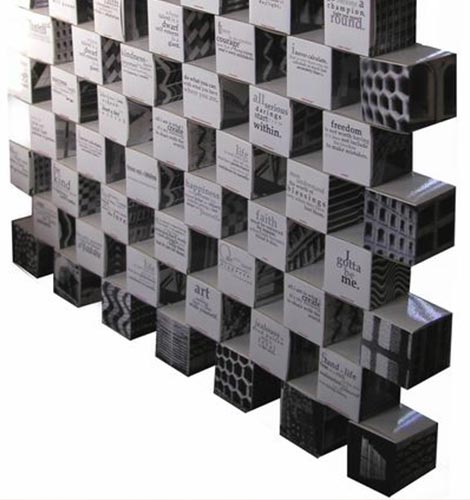

We move on to an artist for whom the interior and the exterior exchange valency. Prajakta Potnis grows, rather than builds a site-specific installation that transforms the walls into skin. In the current site-specific installation, she blurs the line between architecture, nature and the human body creating environments that address the processes of a landscape’s growth and change, as much as they do the body’s cycles. Landscape for Potnis is calibrated along a scale of intensities: it can be as intimate as skin, as distant as mountains framed in a window. What unites these intensities is Potnis’ horror of the violated surface, the membrane threatened by external impact or internal disquiet. She dwells on pore-punctuated skin, painted walls whose wiring suddenly jerks alive, the smoothness of organs that conceal cysts and lesions. This time around Potnis has ambitiously worked with scale and material to create a seven-foot silicon floor sculpture that breeds like a concealed malignancy. The trope of disturbance, for Potnis, is excrescence: as rash or acne on skin, as tumours within the body, as denuded mountains and quarried hillsides. [3]

This exhibition includes voices from the North-east, rarely heard in mainstream Indian discourse or seen in the festive ambit of contemporary Indian art. India was a country of elsewheres and elsewhos even before the digital revolution inaugurated the fashion of cryptonyms and second lives. Cartographically, the North-east is shaped like an arm that refuses either to swing straight or be amputated, dangling from a body that will neither claim it nor let it go. The seven states of the North-east have suffered the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, the AFSPA, for many decades: curfews and crackdowns punctuate normal life, and bomb attacks and battles between the armed forces and militants of various shades are routine events. Emergency is the most typical shape that normality assumes in the North-east.

Sonal Jain and Mriganka Madhukaillya, who live in Guwahati and are co-founders of the Desire Machine collective, achieve a memorable degree of political attentiveness in their video poems by relinquishing all devices that are obviously political. For Jain, the idiom of the urban documentary becomes a point of departure to be thoroughly recast and reinvented. In her flaneuresque contemplation of implied landscape, she transmutes a streetscape in Shillong – ‘discovered’ through seemingly chance encounters around lottery stalls, moving traffic, loiterers and busy people – into a river song. Fluid as a dream, drenched in shades of limpid aqua and bleeding green, the visuals are edited rhythmically to the lapping of waves and the splash of oars. The tender lyricism of this video work belies its philosophical complexity. The riverine metaphor emphasises the need for a confluential multiplicity of ideas, cultures and positions in a society wracked by violence.

By turning the city’s spatial patterns into the flux of a river, by inviting us to read land as water, and by cuing us into re-interpreting the visual subliminally through the acoustic, Jain orchestrates several subtle shifts in our viewerly assumptions. Turned into a river, the city is shaken loose from the competing regimes of surveillance and terror. It flows freely, like poetry, blood or the desire for emancipation. Geared to operate at a subliminal level, the film literally occupies a threshold space. The number 25/75, proclaiming the winning lottery of the day, is repeated like a visual mantra. Its random appearance could suggest the probability of victory but also of plain survival; and it speaks, also, of the ever-present tension between majority and minority, elite and subaltern, winners and losers. Jain generates the moving allegory of a landscape where freedom is furtive, chance is worshipped, and any moment may throw up a transformative encounter with fate.

*

For Mriganka Madhukaillya, abstraction becomes a route to speak the unspeakable: to voice the breath that is choked, to indicate the window that can never be opened, and if opened, will only confront you with the darkness within. In ‘Passage’, he draws us into the spirit and textures of a threatened society and ecology, using the motifs of twinning, partition, rupture and suturing. The film focuses on a single window in the Chaudhari Bari (the House of the Chaudharies) an old haveli in Baruipur, in the southern 24 Parganas district of West Bengal. It is an optical experiment that records the properties of light coming through the wooden slats of a window, the subtle shifts effected by the movements of shutter and pane, with light and breath becoming interchangeable with one another.

The sound track, built from the magnifications of breath, underlines the struggle of a restless body in a prison-like atmosphere suffering from sensory deprivation. The mirages of light are masculinist in tenor, vertically oriented columnar, spire- or linga-like. But they are never stable: they are repeatedly subjected to tremors, pulled apart, violated and abruptly banished into the dark. To explain this cycle of repetition and disjuncture, Madhukaillya cites Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, as questioning “whether repetition should be considered as the throb of Eros or should instead be seen as something that lies beyond pleasure, threatening it with violence – something that must therefore be identified with death.” [4]

But all is not bleak. The yogic operations of breath, composed with a telegraphic yet allusive intensity, lead to the occasional epiphany signalled by the clang of a temple bell or the hint of a lama’s chant. Madhukaillya’s vision is auratic in its etymological multiplicity: it is breath, as well as gold, as well as light.

Notes and References

- Nancy Adajania, ‘The City in Reverse: Prajakta Palav Aher’s Image Rotations’ (exh. catalogue essay; Delhi: Vadehra, 2009). See also, Nancy Adajania, ‘Bonsais or Bullets: Prajakta Palav’s Oblique Portraits of the Middle Class’ (exh. catalogue essay; Bombay: Gallery Beyond, 2005).

- The present author held an Independent Research Fellowship from Sarai-CSDS in 2004-05. ‘Yatra’ is based on her research into the digital transmutation of the family portrait in urban India. See Nancy Adajania, ‘In Aladdin’s Cave: Digital Manipulation and Transmutation of the Private Image in Urban India’, in Iris Dressler and Hans D. Christ eds., On Difference #3, Raumpolitiken/ Politics of Space (Stuttgart: Wuerttembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart, 2008).

- Nancy Adajania, ‘Conceptual Humidity’ (exh. catalogue essay; Bombay: The Guild Art Gallery, 2009). See, also, Nancy Adajania, ‘The Spell of Objects’ (exh. catalogue essay; Bombay: The Guild Art Gallery, 2006).

- Pers. comm., April 2009