Architectural forms and the spaces they create can be the greatest expressions of human thought and emotion. As the architect Balakrishna Doshi has said, architecture is the creation of “the stage set for the theatre of living” and it is here where our dramas and passions, tragedies and comedies are enacted. Much of the architecture we live in, unfortunately, is mundane and uninspired yet the experience of the greatest of buildings stays with us long after we have departed from them, their effects palpably retained by both our bodies and our minds.

Pooja Iranna has long been interested in architecture and the representation of it. In her art she has both attempted to communicate something of the power and presence of architecture as well as employed images of architecture as metaphors for society and her own personality. Previous series of works were directly inspired by the experience of the Mughal monuments in her home city of Delhi, the synthesis of geometrical forms that are both structure and ornament and the seemingly organic nature of these mathematical paradigms. As if creating details from Mughal structures, the artist has built up elaborate relief works which are both picture and object, resembling a portion of a labyrinth and the complex interweavings of the multiple personal relationships each of us juggle. Culled from both craft traditions and modernist abstraction, these relief works celebrated a fragility of materials and a discipline of program, rendering the ancient and anonymous into the contemporary and individual. Through these works, the artist felt that patterns in her own behavior and attributes of her own psyche could be expressed and compared with those of others, bridging the divides of time, space and perspectives with other human beings.

More recently, Pooja has been attracted to modern and contemporary architecture and their potential for creative manipulation. The geometrical complexities of Islamic architecture has given way to a Modernist grid and its permutations, a more straight-forward geometry perhaps but one still loaded with significance. Artists such as Sol Lewitt, Agnes Martin and Carl Andre exploited the potential of the grid in art practice some thirty years ago but today, with the advent of post-modernism, computer technology and digital imaging, the grid has taken on increased ambiguities and associations. Pooja’s interest in the grid has been in the possibilities for unlimited variations within its repetitive structure, in its accommodation of idiosyncrasies and its merging with other forms and structures. Windows, doors and staircases often break the regularity of the grid, to say nothing of the reflections found within the glass skins of many buildings or the pulse of life which moves through them.

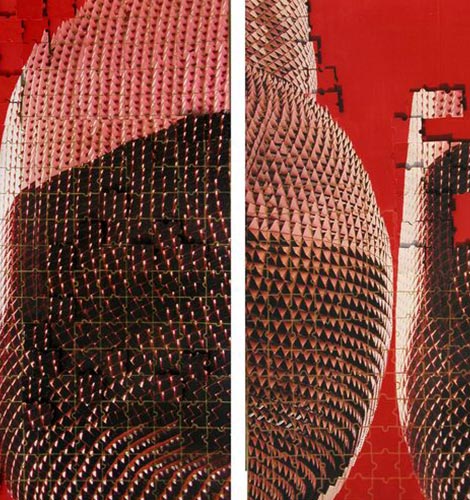

Like many artists of her generation, Pooja has begun to explore the camera as a tool for sketching, record keeping and manipulation. In her most recent works, she has photographed details of architecture and rearranged the colors and lines of these details on the computer. This enables the artist to both personalize the architectural details and to allow the attributes of chance and discovery to shape the final picture. Pooja takes pleasure in allowing this evidence of distortion by technology to remain visible in her work, to both refine and adapt the original details and to comment on man’s increasing dependence on technology for his own self-image. The artist feels this technique mirrors the refinements in her own life in the past few years, reflecting the maturation which has come with motherhood and the focused concentration she has been able to bring to her own art practice.

The works themselves are kept miniature, almost in defiance of the gargantuan scale of architecture, as if one is examining a city through a microscope. Contradictory to what may be one’s expectations, the digitally-manipulated pictures are messier and rougher than the watercolors from which they begin, colors are both stranger and softer, line work feels more organic than in the originals. Pooja is fascinated by the pulsating rhythms which emerge through these processes, harmonies seem to form easily out of the geometries of the architecture while a notational scripture for the patterns of life, or even the synapses of the brain, is achieved. These works become something of a meeting point between the experiments of the first generation of Minimalists in the 1960s and 1970s and the elaborate detailing of palaces and forts found in Rajput and Mughal miniatures since medieval times.

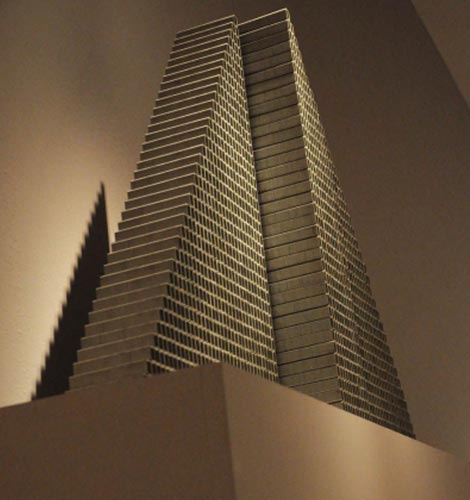

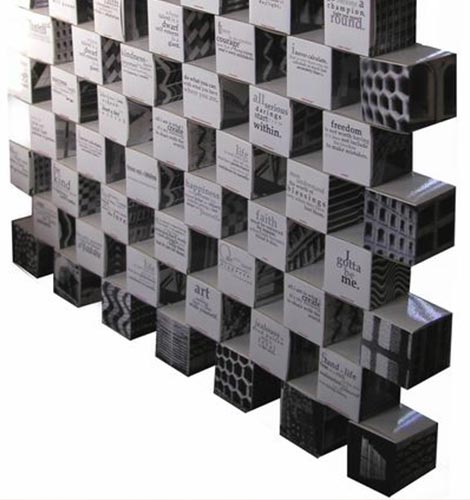

The camera has also allowed Pooja to extend her investigations away from the wall and into three-dimensional space, an appropriate direction for the investigation of architectural imagery. Photographs of the skins of contemporary buildings have been digitally manipulated and repeated, becoming the faces of cubes that are stacked on top of each other slightly askew. A parody of skyscrapers, of course, but also a formal exercise in the potentials of opticality as the solidity of the structure melts behind the flickering staccato imagery which sheaths it. With these works, an interplay of flatness and volume is their proscribed goal, a study in the vibrations of opposites and the viewer’s attempt to resolve these polarities. Fragility and transience also inspire these works. Pooja takes pleasure in the quick assembly her manner of construction allows, as if the temporary and transportable natures of the homes of nomadic tribes have been applied to urban office buildings, a perhaps fitting design solution in these days of globalised business and decentralized offices.

In summation, Pooja Iranna’s works may seem highly iconoclastic in the context of an Indian art scene still very much infatuated with the human figure. Yet her works, though entirely devoid of human images, are very much about the consciousness of the figure and its placement in and experience of space. This experience is both physical and visual, both in real time and in memory. Pooja’s work attempts to trace the effects of architecture on the emotions and the psyche, attempts to find traces of our emotional and psychological lives in the structures and patternings of architecture. Her’s is a struggle to find unique expressions of her own experiences, to acknowledge the distortions and manipulations that play with our emotional lives, and to create elaborate scenarios through an economy of means.

PETER NAGY IS A WRITER AND ARTIST OF INTERMATIONAL REPUTE. HE ALSO IS THE DIRECTOR OF GALLERY, NATURE MORTE BASED IN NEW DELHI.